In the healthcare business, billing and coding are often mentioned together. Yet for those running practices, hospitals, or large physician groups, it is essential to understand their distinctions. Coding forms the foundation translating what care was provided into standardized codes. Billing builds on that foundation using those codes to submit claims and collect payments. Missteps in either process can disrupt revenue flow, trigger regulatory issues, or damage reputation.

What is Medical Coding?

Definition & Purpose

Medical coding is the process of converting the details of patient care diagnoses, procedures, treatments into standardized alphanumeric codes. These codes (e.g. ICD, CPT, HCPCS) allow for uniform communication with payers, support statistical analysis, inform public health strategies, and serve as the basis for claims submission. Without precise coding, billing cannot proceed reliably, and the downstream financial and legal risks multiply.

Common Code Sets & Standards

The dominant code sets in the U.S. include the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10-CM for diagnoses, and soon ICD-11 in transition), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) maintained by the American Medical Association, and HCPCS levels for supplies, non-physician services, and durable medical equipment. These sets are updated regularly. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes policies and updates to assist coders in staying current.

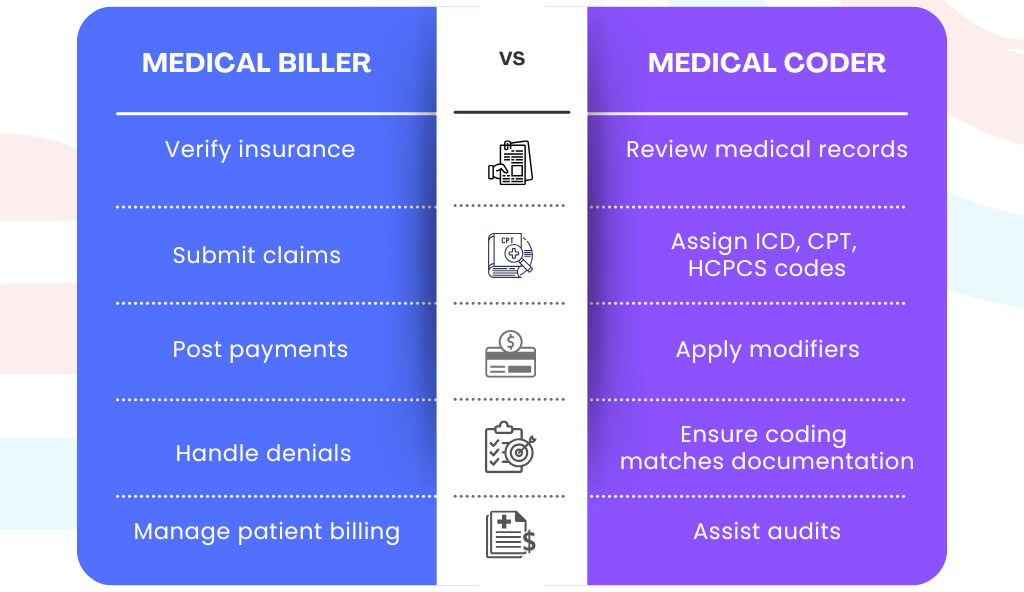

Key Responsibilities of Medical Coders

Coders review clinical documentation, including physician progress notes, lab reports, operative reports, and diagnostic imaging. They must ensure documentation supports the codes used, that specificity is maximized, that appropriate modifiers are applied, and that codes are linked correctly (for example, ensuring the procedure relates to the diagnosis). Coders take part in audits, help with provider queries where documentation is insufficient, and often play a quality control role in minimizing errors like upcoding or undercoding.

What is Medical Billing?

Definition & Purpose

Medical billing is the financial arm of the RCM process. Once services are coded, billing professionals use those codes, together with patient insurance information, to prepare, submit, and follow up on claims with payers. They also interact with patients (for statements, balances, co-pays), track payments, post payments into accounts, handle denials, appeal when necessary, and manage the accounting side of revenue collection.

Core Tasks & Workflow

Billing starts early: before or at the time of patient registration, confirming insurance coverage, benefits, patient responsibility. After the visit and coding, billers assemble claims, ensure proper claim forms or electronic submission (via X12/837 or appropriate institutional forms), check payer rules, submit claims, then follow up on adjudication. Payment posting tracks what was paid, what remains. If claims are denied or underpaid, billers must investigate, appeal, and manage patient billing. Good billing reduces Accounts Receivable (A/R) days and ensures cash flow.

How Billing and Coding Interrelate in the Revenue Cycle

From Patient Encounter to Payment

Every patient encounter starts with clinical documentation. Coders interpret that into coded data. Billers use that data to create a claim, submit to payers, wait for adjudication, then receive payment or denial. If denied, billing works with coding to correct and resubmit or appeal. After insurance pays, patient may receive a bill for remaining responsibility. So, billing & coding form successive phases of the revenue cycle.

Where Errors in One Affect the Other

Coding mistakes such as assigning nonspecific diagnosis codes, missing modifiers, or misinterpreting documentation—lead to denials, delays, or underpayments. Billing mistakes incorrect patient insurance info, late filing, not following payer requirements lead to rejections or slow payments. Together, these errors reduce “first pass yield,” increase administrative burden, drive up A/R days, and erode margins.

Education, Certification & Skills for Billing and Coding

Required Training & Credentials

Coders often require deeper formal training. Many have certificates, diplomas or associate degrees; certifications include CPC (Certified Professional Coder), CCA (Certified Coding Associate), CCS (Certified Coding Specialist), or other specialty designations. Billing roles sometimes require less formal qualifications, though many billers also pursue certifications (e.g. Certified Professional Biller, CBCS) to validate knowledge and increase credibility. Employers increasingly expect that staff stay current on updates in coding and payer policies.

Skills & Traits Needed

For coding, detail orientation, medical terminology, anatomy/physiology, ability to analyze complex documentation, discipline, and ability to work independently are critical. For billing, strong organizational skills, understanding of payer rules and payment policies, communication (with patients, providers, payers), follow-up persistence, and sometimes negotiation skills. Executive leadership also values ability to monitor metrics, oversee audits, and manage workflows between coding and billing.

Common Mistakes, Compliance Risks & How to Mitigate Them

Frequent Coding Errors That Cost Practices

Errors such as using non‐specific or “unspecified” diagnosis codes when more precise codes exist, missing or misused modifiers, mis-linking diagnosis and procedure codes, wrong E/M service level, failing to apply Present On Admission (POA) indicators, overcoding or undercoding. These lead to denials, clawbacks, and penalties. Guidance from the American Medical Association highlights how even small coding oversights can have significant revenue impact.

Billing Mistakes and Financial Risks

Mistakes in billing commonly include submitting claims after timely-filing deadlines, misentering insurance information, failing to follow up on denials, sending incorrect patient statements, or not applying contractual payer discounts properly. These errors slow payment inflow, increase administrative costs, and often reduce overall reimbursement.

Regulatory & Audit Risks

Regulatory risks are serious. Intentional misrepresentation (fraud), but even unintentional errors (abuse) can draw audits, fines, and sanctions. Laws like the False Claims Act, rules from CMS, payer contracts, and HIPAA requirements (with regard to documentation, use of provider identifiers, patient privacy, etc.) matter. Mitigation involves internal audits, documentation improvement programs, keeping staff trained, and ensuring policies are kept current with payer and regulatory updates.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) & Metrics for Doctors and Executives

What to Measure

Measuring the right metrics gives visibility. Key metrics include First-Pass Claims Acceptance Rate, Days in Accounts Receivable (A/R), denial rate and denial resolution time, audit error rate / coding error rate, cost per claim (including cost of denials and reworks), and net collection rate (what % of total charges are collected). Monitoring documentation lag (time from encounter to documentation completion) is also important.

Benchmarks & Targets

Good benchmarks differ by setting (physician practice vs hospital). For many practices, a first pass clean claim acceptance rate above 90% is considered strong. A/R days for well-managed practices often average 30-45 days; higher indicates problems. Denial rates less than 5–7% are often targeted. Cost per claim or cost of rework depends on staffing, software, and volume. Regular internal or external benchmarking is essential.

Best Practices & Technology Tools

Documentation Improvement Programs

Because coding depends on documentation, physicians and clinical staff should be trained to document in ways that support coding (e.g. specificity, clarity). Use templates, alerts in the EHR, provider queries when notes are insufficient. Regular feedback on documentation quality helps.

Use of Software, EHR, Claim Scrubbers & Automation

Modern tools can catch missing modifiers, coding inconsistencies, and payer rule violations before claims are submitted. Electronic Health Record (EHR) systems integrated with coding modules, automated claim scrubbers, and denial analytics help prevent revenue leakage. Technology also supports remote coding and distributed work, but only if workflows are reliable and oversight exists.

Staffing Models: In-house vs Outsourced vs Hybrid

Some practices or hospitals prefer in-house teams for greater control. Others outsource coding or billing (or both) for cost savings, expertise, scalability. Hybrid models combine both. In evaluating models, consider the cost, turnaround times, control, audit risk, data security, and compliance.

Case Example: From Mis-Coding to Improved Revenue

Consider a mid-size multi-specialty clinic where coding for Evaluation & Management (E/M) services was frequently using mid-level codes (e.g. CPT 99213) when documentation supported a higher complexity (99214). The clinic saw a denial rate of 12% for E/M claims due to under-coding or insufficient documentation. By implementing a documentation improvement program, enhancing EHR templates, and introducing claim scrubbers, they increased their first-pass clean claim rate from ~82% to ~95% over 6 months. A/R days dropped by 20%, and annual revenue increased by several percentage points without increasing patient volume.

Conclusion

For healthcare executives and doctors, billing and coding are two sides of the same revenue coin—but each demands specific attention. Coding requires precision, up-to-date standards, and good documentation; billing demands process discipline, efficient workflows, and strong follow-up. Neglect either, and revenue leaks, compliance risk, or audit exposure become real threats.

Action steps:

-

Audit your coding and billing workflows to identify frequent errors and bottlenecks.

-

Build or refine a documentation improvement program involving physicians, coders, and auditors.

-

Invest in or upgrade technology (claim scrubbers, dashboards) to catch issues early.

-

Track the KPIs above, set targets, monitor progress monthly.

-

Ensure staff are trained and certified; keep up with regulatory or payer policy changes.