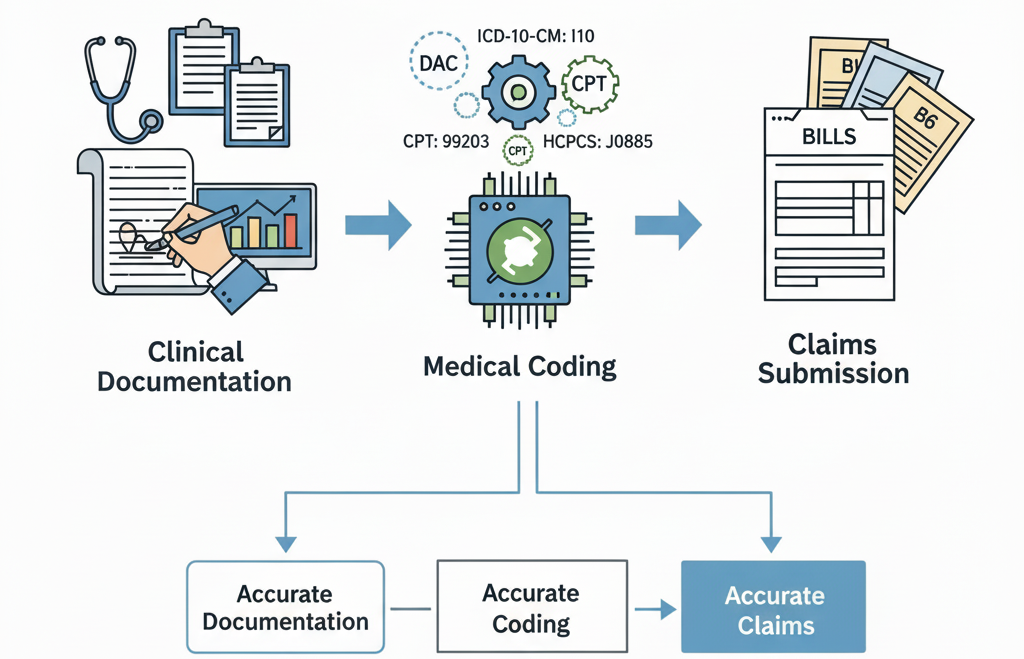

Medical coding refers to the systematic process of translating clinical documentation into universally understood alphanumeric codes. This includes diagnoses, procedures, medical services, medical equipment, and supplies. These codes are then used to submit claims to insurance companies or governmental payers, to track epidemiological data, to support population health programs, and to ensure accurate record keeping. In contrast, healthcare coding is often used interchangeably with medical coding but can imply broader use in analytics, compliance, and value-based care beyond just billing.

Doctors, healthcare executives, and RCM leaders should understand that coding is not just a back-office function: it's central to financial health, risk management, compliance, and patient care continuity.

Definition & Key Concepts

Medical Coding vs Healthcare Coding vs Documentation

Medical coding is the specific act of converting clinical documentation into codes. Healthcare coding is a broader term encompassing all uses of coded data—billing, quality reporting, research, outcome measurement, population health, etc. Documentation is the foundation: if physicians and other clinicians do not document accurately and completely, the coder has no reliable information to translate into codes. Inaccurate documentation leads to under-coding, over-coding, denials, or compliance exposure.

Who Does Medical Coding? Roles & Responsibilities

Medical coders may be internal staff, outsourced service providers, or clinical documentation specialists. Their responsibilities include reviewing patient charts, interpreting physician and allied health provider documentation, selecting the correct code(s), applying modifiers, ensuring codes meet payer and regulatory requirements, auditing past claims, and collaborating with clinicians to clarify documentation. Coders must often stay current with code set revisions, payer policies, and regulatory guidance.

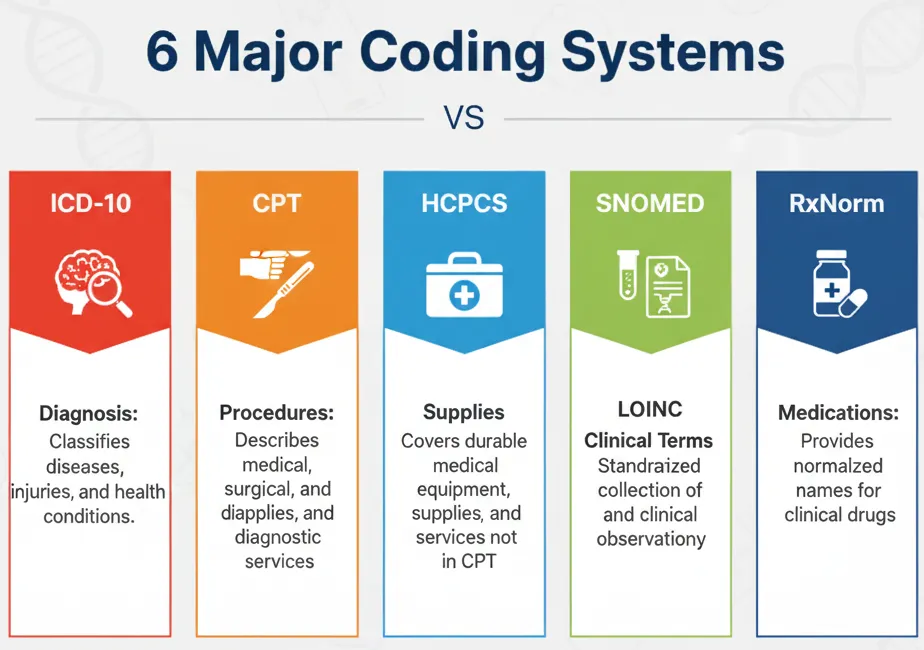

Major Medical Coding Systems in the U.S.

Several coding systems are used together to provide comprehensive coverage for diagnoses, procedures, supplies, and so forth.

ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS

The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) is used for diagnosis coding in the U.S. and is maintained jointly by NCHS and the CDC.

ICD-10-PCS (Procedure Coding System) is used for inpatient procedure coding. Comparisons of what was billed vs documented is often a pain point for hospitals.

CPT (Current Procedural Terminology)

Maintained by the American Medical Association (AMA), CPT codes describe medical, surgical, diagnostic, and radiation procedures and services. It’s widely used for outpatient and provider-based services. Current revisions and the use of modifiers are crucial to maintain accuracy.

HCPCS Level I & Level II

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) includes:

-

Level I = CPT codes

-

Level II = non-physician services, supplies, durable medical equipment, ambulance, etc., not covered under CPT. Used broadly in Medicare/Medicaid contracting.

Other Systems: SNOMED, LOINC, RxNorm, Emerging Terminologies

For purposes beyond billing—clinical documentation, interoperability, laboratory tests, and research—coding terminologies like SNOMED CT, LOINC, RxNorm are used. They support clinical decision support systems and outcomes research. Many health systems map between these terminologies and billing code sets.

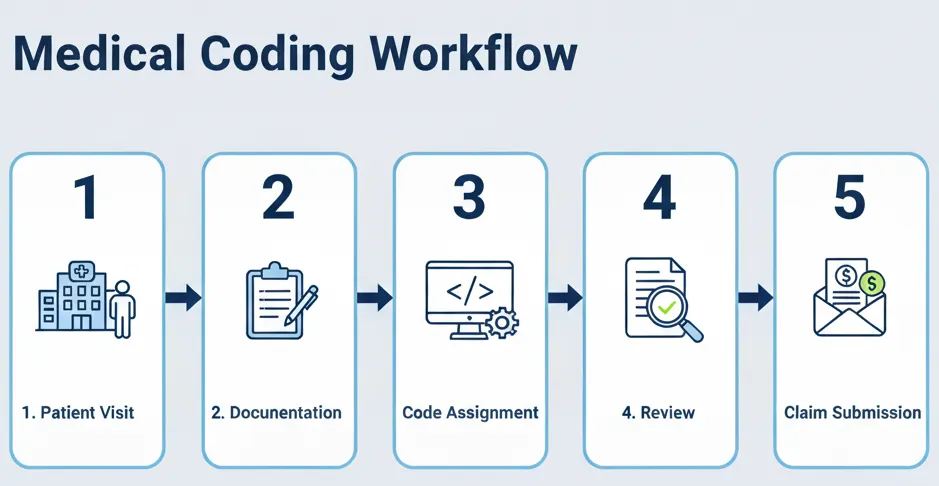

The Medical Coding Workflow

Understanding how coding fits into the revenue cycle helps doctors and executives optimize both financial performance and compliance.

From Clinical Documentation to Code Assignment

The process begins when a patient encounter occurs. The physician documents history, examination, diagnosis, procedures, orders for labs/imaging, etc. These records are collected. Coders then review the full documentation, abstract relevant details (diagnosis, procedure, date, provider, setting, modifiers). They assign codes according to the relevant code sets (ICD-10, CPT, HCPCS, etc.), apply modifiers when required, check documentation for compliance, and prepare for claim submission.

Role of Clinical Documentation Improvement (CDI)

Because documentation is often insufficient or ambiguous, CDI programs work to improve the quality, completeness, and specificity of physician documentation. CDI specialists help bridge gaps between what was done and what was documented. This can include queries to physicians to clarify ambiguous or missing information. Strong CDI helps reduce denials, underpayments, and audit risk.

Audits, Edits, & Claim Submission

After coding, internal or external audits review accuracy and compliance. Payers enforce edits (e.g., National Correct Coding Initiative, Medically Unlikely Edits) that check for improper bundling, misuse of modifiers, or improbable units. Claims are submitted electronically, often with checks in place, and then reviewed by payers for medical necessity, correct coding, and documentation. Rejections or denials can result if coding does not align with documentation or payer policy.

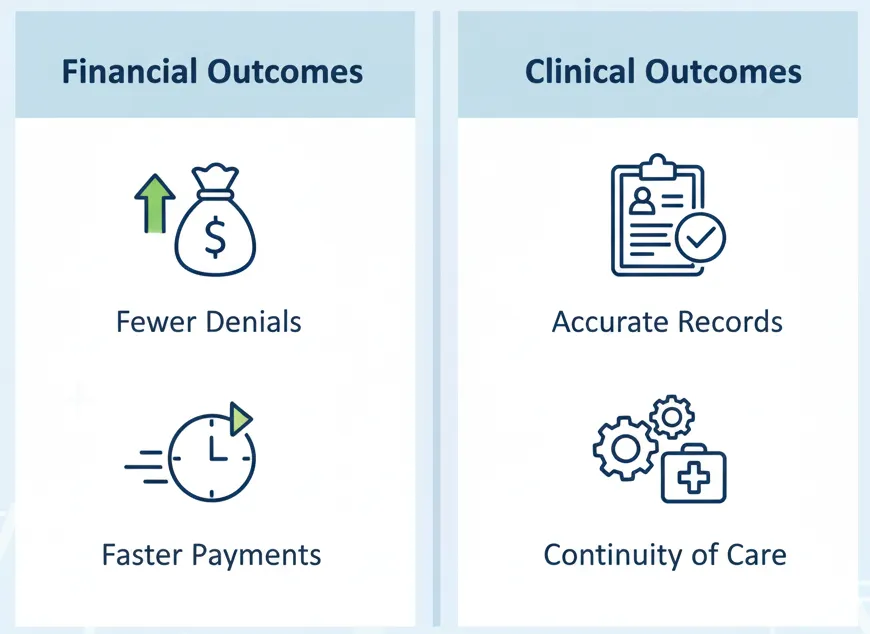

Why Medical Coding is Critical

Revenue Cycle Impact

Accurate coding directly affects reimbursement. Under-coding leads to lost revenue; over-coding can lead to denials or even regulatory penalties. Also, denials cost time and resources to correct. Proper coding accelerates claim turnaround and cash flow. For organizations managing both volume and complexity, even small inefficiencies can lead to major revenue leakage.

Clinical & Patient Care Impact

Medical coding defines how patient diagnoses and treatments are recorded over time. Poor coding can lead to miscommunication among providers, misinformed clinical decision making, mistaken risk stratification, and suboptimal care transitions. It also affects whether a patient’s past history is accurately captured, influencing treatment, referrals, and follow-ups.

Data Reporting, Public Health, Value-Based Care

Coded data fuels quality measurement, public health surveillance, epidemiology, and population health management. It supports research, informs policy, and underlies value-based contracts and risk adjustment models. Payers and regulators rely on accurate coding for metrics like readmissions, complication rates, and outcomes. Errors in coding can distort these metrics, harming reputation, compliance, and reimbursement.

Compliance, Risk, & Regulatory Considerations

HIPAA, PHI & Documentation Requirements

Medical coding must comply with HIPAA’s Privacy Rule, ensuring that Protected Health Information (PHI) is handled securely. Documentation must also preserve necessary clinical details, while avoiding unnecessary or inappropriate information. Codes submitted must correspond to what is documented.

Payer Rules & Medical Necessity

Each payer (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers) has policies about what services are medically necessary, what documentation supports them, specific modifier rules, allowed places of service, bundling rules, etc. Understanding local coverage decisions, prior authorizations, and payer policies is essential to avoid denials.

Audits, Penalties, Fraud & Abuse

Health care organizations are subject to audits (by payers, government), and may face penalties for miscoding, overbilling, submitting false claims, or failing to document properly. The False Claims Act, OIG rules, and possible state‐level laws impose risk. Under- or over-coding, when systemic, could invite investigations. Internal compliance programs and periodic reviews are important.

Practical Case Examples for Doctors & Executives

Small Clinic vs Large Hospital Coding Differences

In a small clinic, coders may wear multiple hats, sometimes handling coding, billing, and even claims follow-up. The physician may have more direct involvement. In a large hospital, coding is often specialized (inpatient vs outpatient, by department or service), with separate CDI programs, more sophisticated audit and compliance functions, and stronger tech support (coding software, EHR integration).

Specialty Example: Behavioral Health

Behavioral health has unique coding challenges: many diagnoses are subjective, therapy sessions have specific rules, telehealth is common, privacy is often more sensitive, and payer policies may differ drastically. Accurate diagnosis coding under ICD-10 Chapter V (mental, behavioural, neurodevelopmental disorders) matters both for reimbursement and data analytics. Misclassification or vague diagnoses can lead to denials or underpayment.

Outsourcing vs In-House Coding: Trade-offs

Outsourcing coding can reduce staffing overhead, give access to specialized expertise, and scale quickly. But it can also make oversight, documentation feedback loops, and quality consistency more difficult. In-house coding grants greater control, faster feedback to clinicians for documentation improvements, and potentially lower risk, but often requires investment in training, management, and infrastructure.

Common Challenges & How to Overcome Them

Keeping Up with Changes

Code sets (like ICD-10, CPT, HCPCS) are updated regularly. Payer rules, telehealth modifiers, and documentation guidelines change often. Organizations must invest in continuous training, subscribe to authoritative resources (e.g., AMA, CMS) and enforce document version control.

Documentation Gaps & Physician Engagement

Often the bottleneck is in documentation: missing details, ambiguous terms, or insufficient justification for medical necessity. Engaging physicians with feedback, training, and documentation standards is essential. CDI programs, internal query processes, and leadership support make a big difference.

Technology, Automation & AI: Opportunities & Pitfalls

Electronic Health Records (EHRs), coding tools, Natural Language Processing (NLP), and AI promise to speed coding by suggesting codes, spotting documentation gaps, and doing pre-audits. But over-reliance without human oversight can risk errors, incorrect modifiers, or misinterpretation. Transparency, validation, and human review remain essential.

Future Trends in Medical Coding & Healthcare Coding

Value-based care and risk adjustment will continue to shift how coding is valued and audited. Telehealth and virtual care expansion changes billing and coding rules, sometimes rapidly. AI, machine learning, and automated coding tools are maturing. Interoperability efforts (mapping between SNOMED / LOINC / ICD etc.) will increase for analytics and reporting. Regulatory scrutiny and payer audits are likely to increase, especially around overuse, underuse, and documentation.

Conclusion & Actionable Takeaways

Accurate medical coding is far more than a billing necessity—it is central to your organization’s financial health, compliance posture, patient care quality, and data integrity. For doctors and executives, here are actions to consider:

-

Ensure that documentation standards are clearly communicated, enforced, and periodically reviewed.

-

Invest in or partner with strong Clinical Documentation Improvement programs.

-

Keep current on code set changes, payer policies, and telehealth/virtual care coding requirements.

-

Monitor coding accuracy via regular internal audit, feedback loops, and metrics such as denial rates, undercoding incidence, and revenue leakage.

-

Evaluate whether coding functions are best handled in-house or outsourced given your size, specialty mix, and risk tolerance.

-

Leverage technology (EHR features, coding tools, possibly AI/NLP) to assist coders—but always maintain human oversight for quality and compliance.